Countdown, or Constructing Recession Proof Portfolios

In the 1996 Sci Fi thriller Independence Day, Jeff Goldblum plays David Levinson, an overeducated cable television technician. He notices a signal buried within the geosynchronous orbit of the communication satellites orbiting the earth. He also notices that the signal is slowing down to a stop.

“The signal hitting the satellite feed is slowing down to extinction…Countdown.”

How are we to make sense of all the recent economic data that points to an impeding recession? Traditional indicators (such as the Sahm Rule, the inverted yield curve, and the ISM Manufacturing Index) have been flashing red for some time. Some for well over a year.

What’s more – by nearly every measure, the current US domestic large cap equity market is overvalued.

And yet, since the recession that everyone expected last year seemed to have dissipated, inflation has cooled from its 2022 highs, and the S&P 500 started another upward trend as of October of last year, which resulted in a positive 24% return for calendar year 2023, most of us are willing to believe in the ever-growing prospect of a soft landing.

Are we headed into a recession? What will be the catalyst that begins the economic downward spiral? Is it possible to build a recession proof (or at least recession resistant) portfolio?

With the Trump/Harris election showdown in less than two months, and many market pundits discussing not only a downturn in the markets, but a historic bubble across all asset classes, it’s important to review certain facts before making an emotional decision.

Are We Headed Into A Recession?

“The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent” is a quote attributed to John Maynard Keynes. This idea encapsulates much of the confusion surrounding the current market environment. With the exception of 2022, the US large cap equity market (measured using the S&P 500) has been positive every year since 2009, giving us one of the longest bull runs the market has seen.

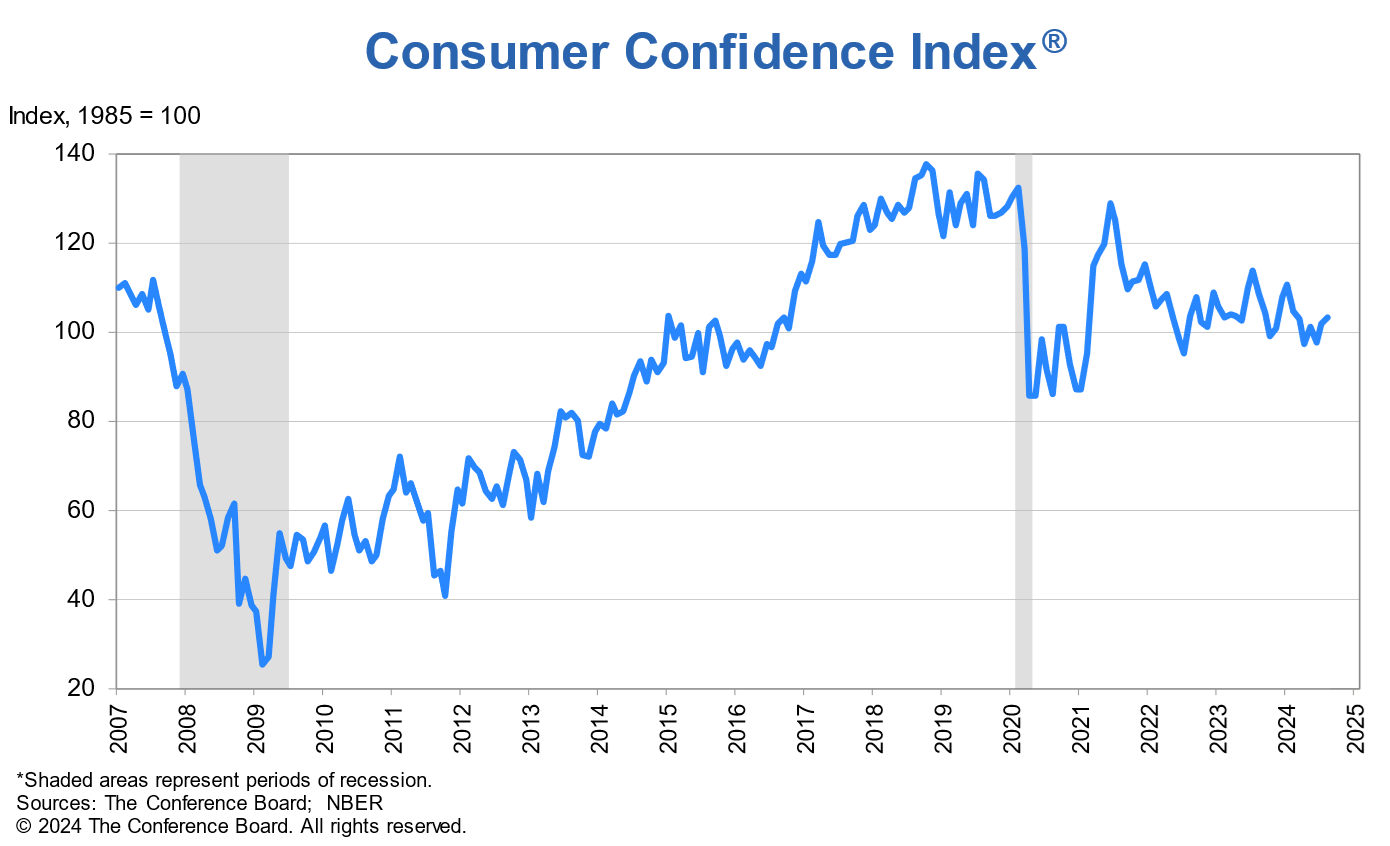

Yet, consumer sentiment is not commensurately stellar:

What can explain this disconnect?

The Fed’s intervention is one of the main components of this decoupling of the greater economy from the stock market. 2020, the year of the global pandemic, showed us this. Much of the global economy was in recession during this time, since economic activity ground to a halt. Yet, risk assets (such as stocks, cryptocurrencies, and even NFT’s) all rose in value precipitously.

Using data points from those asset classes to predict how the economy was going to rebound was something very challenging, since it was anybody’s guess how the pandemic was going to shape the remainder of the 21st century.

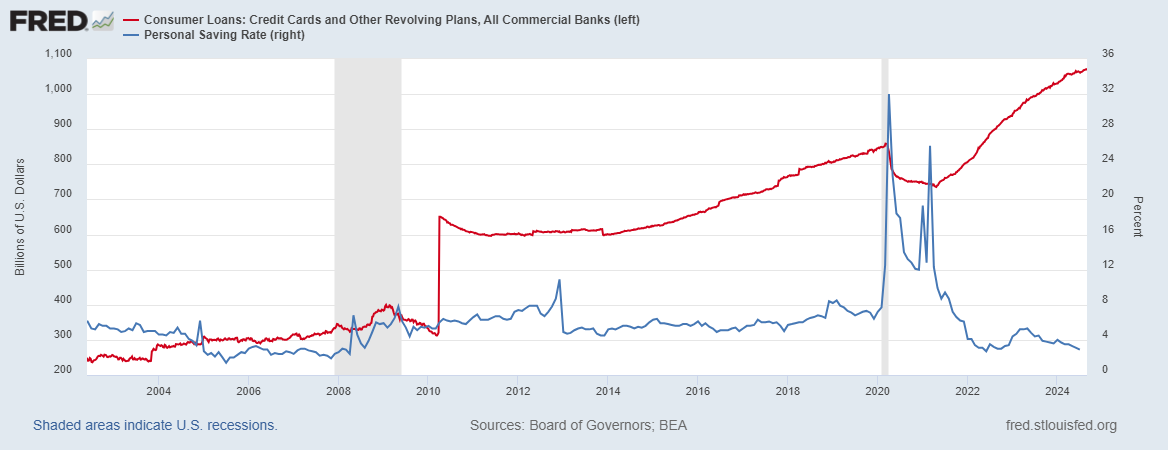

The recessions evaporated as many began to return to work (albeit remotely), and consumer spending began accelerating (at the expense of savings, and with an increase of leverage through an explosion of credit card debt):

And yet, the Fed’s movements (raising rates to curtail inflation) were again integral to market returns. Increasing rates to slow down consumer spending had the effect of lowering bond prices, but the stock market also suffered, giving us one of the few years in market history where both stocks and bonds suffered negative returns. This blew a hole in the traditional 60/40 portfolio, leaving nowhere to run to during that time except cash or commodities, which were the best returning asset classes of that year.

And now we’re getting ready for the Fed to move again. How the current market will respond to a decrease in the discount rate (and any quantitative easing the Fed may undertake) is not easy to predict.

Predicting Recessions

Recessions are tough to predict for several reasons:

- They can only be confirmed after the fact. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee is the final arbiter of whether we’ve experienced a recession or not (defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth of GDP). This can only be ascertained once the data has already been evaluated and compared to the prior quarters (which can also be restated upwards or downwards).

- Not all recessions are created equal. For example, 2008’s Great Recession was born of a concentration of economic activity (the housing bubble), which was bolstered by securitization, NINJA loans, and excess leverage. Most recessions are not quite as dramatic.

- Recessions aren’t always evenly distributed across an entire economy. While recessionary calls are made for the overall economy, some parts are more affected than others. For example, those industries that have a “high elasticity of labor supply” meaning that changes in the overall economy can strongly affect their hiring and firing practices, will experience it more strongly than other industries.

To further complicate matters, the decoupling between the S&P 500 and the greater economy (up market with recession in 2020, down market with no recession in 2022) not only muddles the historically high correlation between the two measures, but also calls into question whether this looser correlation will continue to dominate the relationship between the two measures, or if we’ll finally begin to see them coalesce into more familiar territory.

A steep market decline with a comparatively tepid recession is not unheard of. In fact, it’s what was noticed earlier this century, when the economy was in a relatively minor recession in 2001, but the S&P 500 lost 40% of its value from 2000-2002.

If we are to believe that markets are mean reverting, and that economies are cyclical, then a recession is inevitable. The question will become: will the markets perform better or worse in that scenario?

What Could Push Us Into A Recession?

Higher unemployment, leading to tepid economic activity, is the general recipe for a recession. How drastic or sustained these changes become will determine the severity of the recession (as well as any subsequent shocks).

We’re starting to see these factors at play.

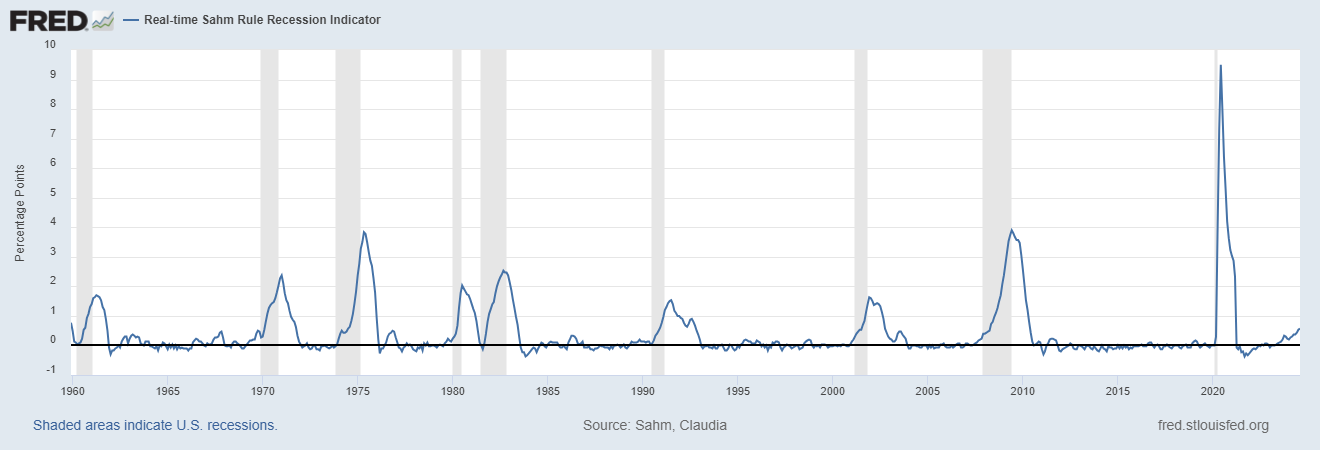

The Sahm Rule, named after ex-Fed member Claudia Sahm, shows us that when unemployment increases by half a percentage point or more over the three month moving average, when compared to the minimum of the three-month averages from the previous 12 months, unemployment quickly spikes, signaling the start of a recession.

Higher unemployment means less disposable income in the economy, leading to less consumer spending, which makes up nearly 70% of US GDP.

An exterior shock could also precipitate a recession: a spike in oil prices, or other commodities and inputs to finished goods, could reintroduce inflationary pressures into the economy, resulting in an adverse impact on consumer spending.

Of course, there’s nothing saying you can’t have both at the same time.

In a recent essay, Claudia Sahm has thrown some water on the recent breach of the Sahm Rule (both due to an increase in immigration skewing unemployment numbers and the Fed spigot opening to make the economy awash in liquidity, thereby rendering many traditional indicators null, or at least impaired).

However, this doesn’t explain the other traditional measures that are also still flashing red.

John Templeton once remarked that, “The four most dangerous words in investing are: this time it’s different. Each bubble (the Roaring Twenties, the Dot Com, the Crypto Craze and now All Things AI) generally relies on the idea that traditional methods of valuation don’t apply due to the exceptionally new nature of the technology. The same was even said about the railroad, before that ushered in another market crash.

However, things would have to really be different for us to forget that momentum never persists, that market bears increase downward pressure on asset prices as they skyrocket, and a garden variety recession may be enough to turn the market into net seller territory at a rapid fire pace.

As the saying goes, “the market goes up in pennies, but comes down in dollars.”

How To Build A Recession Proof Portfolio

Short Answer: it’s not possible.

Caveat: that’s not the same as saying there’s nothing you can do.

As we mentioned before, not all recessions are created equally, so to know exactly where to allocate your funds to stave off the short-term overreactions generally seen in the leading stages of a recession requires the foresight of a fortune teller.

An investor might decide to make a high stake, high conviction (and high risk) trade shorting the domestic large cap equity market (and much like the famed traders noted in works such as The Big Short, they could win a small fortune, as well as bragging rights). However, the precision required in timing the trade, as well as being able to withstand the bullish pressures running against your position and the daily increasing carrying costs, make this equivalent to gambling in a casino without the complimentary beverages.

Conversely, a higher allocation to fixed income and defensive stocks is a traditionally smart move in a recessionary environment, until you consider that a quickly depreciating dollar and excessively historic debt (both public and private) may result in negative returns across the board - similar to 2022, only with more accelerated and extreme movements.

International and emerging markets stocks and bonds have provided some non-correlated relief in past domestic market routs. However, with China facing many of the same recessionary pressures as the US, and the volatility of the dollar providing an extra level of risk when investing overseas, these sectors may underperform as well and fail to provide an adequate hedge.

As far as cryptocurrencies: they don’t have enough history to make a high probability educated guess as to how they’ll perform in an environment where all other asset classes have failed. Many of the narratives given to support the parabolic growth of bitcoin prior to 2022 (e.g., it was a hedge against inflation, a hedge against the frailty of fiat currencies, had price support by a global network of investors in a perpetual HODL pattern, and had an increasing acceptance as a means of payment) all fell short when investors using them as a diversifier needed them most.

Which brings us back to our original question: what is to be done?

While keeping in mind that all portfolios should have a strategic allocation (meaning one that reflects one’s risk tolerance, time horizon, and economic forecasts), there are steps investors can take to help ensure their portfolios are more reflective of their goals:

- Honestly assess how much excess risk you’ve undertaken in the past few years. Most all investors are plagued by both risk aversion and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). This explains the majority of bad decisions in portfolio construction. Investors need to be honest with themselves: did you load up on Tesla or Nvidia because of the huge run ups in price? Have you asked yourself: how would I react if I saw my portfolio decrease by 30%? Word to the wise: if you hold more than 60% in equities and don’t believe that such a decrease is possible, you’re likely are more aggressively allocated than you thought. After 2008, when interest rates fell to zero, most of us were pushed out higher onto the risk continuum because there were few alternatives to have your nest egg outpace the increasing cost of living. The last two years have presented investors with low-risk investments yielding 5% or more of which not everyone took advantage. Ask your advisor for a risk tolerance questionnaire and complete it. If your portfolio is riskier than it should be after grading the questionnaire, this is a very strong indication that you’ve been too attuned to your FOMO inner voice.

- Practice risk management. “The dumbest reason in the world to buy a stock is because it’s going up” is one of the myriad kernels of investment wisdom handed down to us by Warren Buffett. Yet, most investors think there’s no more to the investment universe than the large cap equity market, and their portfolios reflect that sentiment:

- Remember sector rotation: no one asset class dominates perpetually, and asset prices move before narratives take hold to explain the rationale behind the move. Much like the way Wayne Gretsky became an effective hockey player, not because he would focus on where the puck was, but where it was going to be, investing in asset classes that are currently out of favor not only diversifies your portfolio, but positions you to be an early adopter of the next best performing asset class.

- Use ETF’s or closed end funds in lieu of open-ended funds. Open end funds are the traditional mutual funds you may have invested in the past through your bank or your 401(k). In some cases, you won’t have an alternative (such as in company qualified retirement plans). However, in an IRA or a taxable account, ETF’s can not only provide strategies that you cannot use in an open-ended construction, but you can also set sell stops on the positions. This sells out all or part of your position as the price declines, limiting your loss and/or locking in your gains.

- Make room for tactical allocations. There’s nothing saying you can’t bet on how you believe markets will move in the short term. The trick is to not allocate so much that if you’re wrong, or too early, it has a detrimental effect to your overall portfolio. Tactical allocations can both diversify and concentrate, so you have to be thorough in assessing the correlation between your short-term ideas and your long-term holdings, However, under favorable circumstances, tactical allocations can add excess risk adjusted returns in very volatile markets.

- Recall that the market is a tool, and not the end result of your financial plan. If you’re old enough to remember Qualcomm’s run in the late 90’s, then you recall that it was the Tesla of its day, just as Tesla may be remembered as the Nvidia of its day. The point is not necessarily to “beat the market” but rather to have your assets grow at a pace that will most likely meet your needs or your goals within the risk tolerance and time horizon desired. Without a plan to provide a context, you’re flying blind and chasing performance for fear of missing out, or outliving your assets, or not meeting your goal, or any of the numerous fears that plague investors of all experience levels.

Lastly, you must be very aware of the practice and experience of investing. Generally, a greed mindset easily shifts into fear, and not quiet observation. The impulse to act in the face of changes in the market environment, and to act quickly, is as common as it can be disastrous. One does not prepare themselves for this psychological onslaught by thinking it won’t happen to them, but by taking steps to make sure they have a plan in place for when it invariably happens to them.

The idea is not to reach a state of investor nirvana, where all adverse market conditions are met with the placid acceptance of a Zen master. Rather, you should make sure your investment mix is appropriate for what you’re attempting to accomplish, and that you’ve taken prudent steps to align the means to the proposed end. That’s the best anyone can do.

The recent volatility in the market seems to point to a fragile, rather than a robust, bull market; with most of the participants eyeing the exits and hoping they’ll be among the first. As of September 6, 2024, the S&P 500 Price to Earnings (P/E) ratio was 28.26. Compared to the historic mean value of 16.09, this suggests that, holding everything else constant, the S&P 500 would have to come down from its closing price on Friday, September 6, 2024 of 5407.75 to 3078.93. That’s quite an adjustment.

If the increasing number of famed and experienced investors calling not only for a downturn, but a catastrophic downturn, are to be believed, and if one is convinced that market returns are mean reverting and economic growth is cyclical, then a recession and market downturn are inevitable.

The wisest course of action may be to adopt the philosophical mindset of the Bard: If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now...The readiness is all. (Hamlet V.ii.234-237).